Pictures: Using the past to record today’s RNLI

Jack Lowe has started his five year Lifeboat Station Project, recording the lives of RNLI crews around the UK and the Republic of Ireland using Victorian photographic techniques. He speaks to YBW about his ambitious plans.

For Jack Lowe, The Lifeboat Station Project is a combination of his love of photography, the sea and the RNLI.

Even from a young age, the professional photographer knew he was destined to a life behind the lens.

“I’ve always been happiest on the water,” he said. “My interest in photography was sparked at just eight years old, from the moment my Grandmother gave me her mother’s Kodak Instamatic camera. I also became hooked on lifeboats around the same time, when my Dad introduced me to Cowes Base on the Isle of Wight – now the Inshore Lifeboat Centre – that made Atlantic 21s at the time.”

A young Lowe joined Storm Force, the RNLI’s junior membership club, wearing “the badge with pride”.

As an adult, he worked for 15 years at “the very highest level as a digital retoucher and printer” and then experienced, what Lowe calls “a mid-life correction”.

“I felt like I’d lost my mojo and the adventurer side to my character that I’d enjoyed as a teenager,” he explained.

After deciding he didn’t want to spend the rest of his working days in a studio in front of computers, he spent several years thinking about his next goal – The Lifeboat Station Project was born.

See Jack Lowe’s pictures of RNLI lifeboat crews below

With his beloved Neena, a decommissioned NHS emergency ambulance which he converted into a mobile darkroom, Lowe began recording the lives of the RNLI volunteers in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

The 12×10 inch Ambrotype of the Oban RNLI lifeboat crew. Credit Jack Lowe.

“This project is incredibly special to me. It’s hard to describe quite how much,” said Lowe. “I’m turning childhood dreams into something meaningful, not just for me but for all those who come into contact with the project.

“I’ve travelled too far down the road to turn back now. There’s no Plan B. It’s all or nothing,” he noted.

Lowe decided to use Victorian photographic methods because he “wanted to make photographs again like when I was a youngster”.

He said: “However, I also didn’t want a two-stage process of film and printing. I wanted the photograph to be unusual in the medium in that I wanted it to be unique. In essence, a sculpture.

“I’ve always had a keen interest in the history of photography, so I knew that left one process — Wet Plate Collodion. Having made the decision, I set about learning the craft.”

The process needs darkroom facilities close at hand, which is why Neena was converted. Lowe said this has also helped the RNLI crews feel engaged.

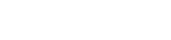

The 10×12″ Ambrotype of the Cromer RNLI Coxswain, John Davies. Credit Jack Lowe.

“The lifeboat men and women are able to step into Neena and witness the magical, beautiful process for themselves. As a result, they leave the station feeling that they’ve been a part of something special, a part of history and enjoyed a day that will live long in their memories,” he explained.

Once Lowe has photographed every one of the 237 RNLI Lifeboat Stations in the UK and Republic of Ireland, the pictures will be showcased in a book and exhibition – all to raise awareness and money for the RNLI.

The Lifeboat Station Project is entirely funded by print sales, poster sales and the support of people interested in Lowe’s work.

Although there is huge interest in the project, Lowe admitted there are logistical and personal challenges with “one of the largest photographic projects ever undertaken in the history of the medium”.

The view from The Mumbles Offshore RNLI Lifeboat Station towards the old boathouse. Credit Jack Lowe.

Wet Plate Collodion has an optimum working range of between 15-24ºC, making the unpredictability of the British climate a challenge. Transporting the large qualities of glass involved was also a difficulty which had to be overcome.

“I can only document around five to eight stations on any one trip. At around ten plates per station, I usually have about 100 12×10 inch pieces of glass on board,” explained Lowe, a married father of two.

Balancing such a huge project with home life can also be tough.

“My family are rooting for me but it can be hard sometimes, particularly as the Project grows in stature. I couldn’t make this work without them being ‘on-side’, that’s for sure,” he said.

But, on his journey, Lowe has made many friends, and has “been humbled” by the RNLI volunteers he has met.

“That kind of sentence can trip off the tongue all too easily but it’s true. Their stories of rescues, their dedication to the task. It’s special. Incredible,” he noted.

He says the crews’ reactions to his work “are extraordinary”

The Tenby RNLI Crew, including Poppy the station dog. Credit Jack Lowe.

“Some people have even been moved to tears when they’ve seen their portrait magically appear from the chemicals. I love that people buy the prints and posters too. After all, that’s the only way the project is funded (I haven’t been commissioned to make the work). For me, that’s the ultimate affirmation that I’m doing ‘the right thing’,” concluded Lowe.

Visit the The Lifeboat Project website or follow the progress via the Mission Map.

Related articles:

Angel Eaglen

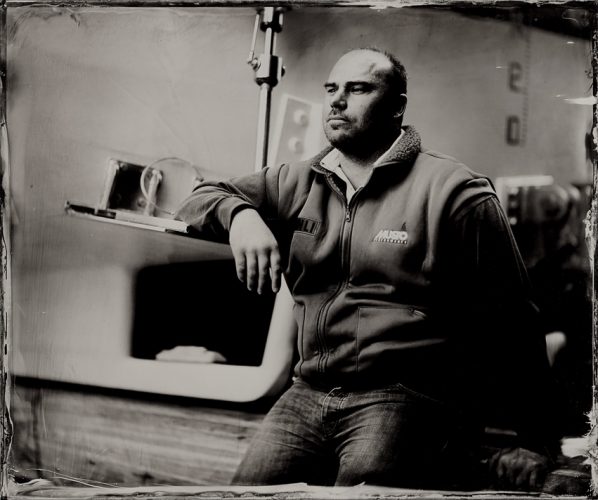

A member of the Wells RNLI lifeboat crew, Angel Eaglen. She joined the crew at the earliest opportunity on her 17th birthday. Just weeks before this portrait was taken, she’d had her first service call and pulled a dead body out of the water, which she tried to revive (in vain).

Credit: Jack Lowe